Less than three weeks after Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election, over 350 people gathered in Lancaster, Pennsylvania for a mass meeting that would evolve into Lancaster Stands Up. We would go on to challenge the frameworks promoted by many Democratic strategists, showing that it is actually possible to use progressive populism to reshape the political terrain in areas that the mainstream media would dismiss as “Trump Country”. This initial meeting was my first taste of organizing, and I wasn’t the only one. I grew up in Lancaster is a small city of 60,000, located in a mostly rural county of the same name. I remember feeling hopeless, trapped in an atmosphere of evangelical conservatism. But that meeting showed that things were changing: in response to the election, neighbors came together from across the county to not just meet each other, but really see each other for the first time. As we sat together, drying off our tears and shedding more, we knew that we were not alone. More than that, we started to have a feeling that we might very well represent a hidden majority in our region. That night, we asked ourselves: Where do we go from here?

We developed an answer: We need to build the capacity to win elections if we are going to turn back this tide and win the deeper changes our communities need. And in spite of what establishment politicians like Senator Tammy Duckworth may think, it is possible for progressive populists, including democratic socialists, to win these races in the small towns and rural areas across this country. Elections aren’t enough, but they are a crucial aspect of the process of power building we need.

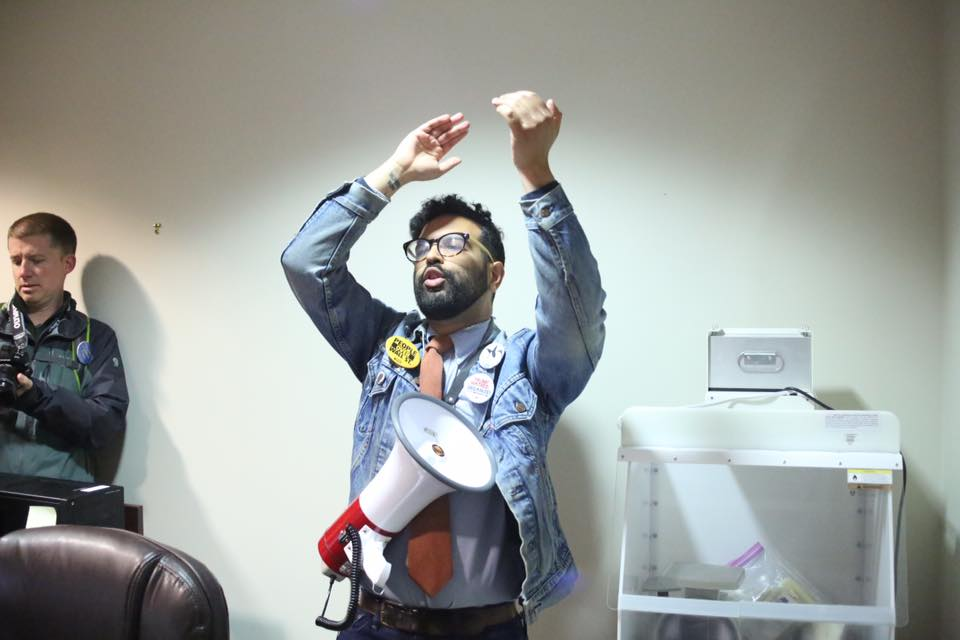

Lancaster Stands Up targeted our newly elected Congressman Lloyd Smucker early on. Congressman Smucker, a Republican former State Senator known for his centrist policy positions including support for DREAMERs, quickly proved he was more interested in towing the Trump party line than representing his community. We would converge in the streets and fill his office, sometimes numbering in the thousands, demanding that he stand up for our community and break with Trump. But that was the least of our demands. Like most Americans, we wanted healthcare for all, a path to citizenship for DACA recipients, and a tax system that benefits working families over corporations. Over time, it became clear that we needed to enter the electoral arena if we were going to address these issues. Smucker’s Democratic competitor was an establishment corporate Democrat who wasn’t tied to the community, and she wasn’t going to stand with us on these issues. And even worse, it wasn’t likely that she would even win in 2018 despite establishment backing and massive financial support. who She had already suffered a decisive loss in the last election. We needed an alternative candidate who could speak to our issues and who could actually win the support of our community.

After holding candidate forums before the Democratic primary, we eventually endorsed Democratic candidate Jess King. King, a community leader with deep local Mennonite roots who founded a nonprofit small business incubator for women and people of color, is running on a progressive populist platform that includes Medicare for All and debt-free public college.Our organizing efforts helped Jess King to effectively rout the establishment competitor in the primary. Now, King and her army of volunteers are set to run a historically tight race against Lloyd Smucker.

Our organization has made extraordinary gains through entering this race, but not everyone in our base was initially convinced by the idea that we should endorse and run candidates. We had a number of debates in our organization between people who wanted us to leave the politics up to the Democratic Party so we could focus on advocacy and awareness-raising, and those of us who wanted to directly contest for political power.

This question – of whether or not to engage in electoral politics – has been persistent and polarizing among the Left across the world. On one side, there are the incrementalist, reform-oriented liberals who insist that elections are the only way forward. On the other side, there is a radical, revolutionary front that rejects electoral work in favor of direct action, above all else. This is an unhelpful and false dichotomy that doesn’t recognize that political struggle takes place in varied contexts. It ultimately serves to divide our efforts and to restrain our political work.

It is true that electoral power and reform alone won’t be enough to win our collective liberation and create a world free of poverty, war, and inequality. But it is for this very reason that we need to gain clarity on the actual benefits and limitations of electoral work. We won’t build enough power win if organizations and movements that share the same values don’t communicate and complement each other’s efforts- in spite of differing strategies and tactics.

Our current political and economic system confines the extent of changes that can be brought about through reforms. Our government was built according to the vision of framers of the Constitution and then shaped the generations of businessmen and politicians who followed. Our system utilizes white supremacy, patriarchy, and imperialism to enact the framers’ desire to maximally benefit and protect the owning class and their property, all at the expense of working people. We can utilize aspects of our current system to improve people’s lives, but we have to recognize that this bar is set incredibly low, given the incredible violence enacted by our healthcare system and the prison-industrial complex alone,. We need a fundamental transformation of our system if we are going to attain equality and liberation for all people.

That doesn’t mean that electoral power is a dead end. In fact, it’s a strategically necessary path that is key to creating openings for the even deeper change that we need. Right now, our organizing potential is incredibly limited because of decades of right-wing victories in the cultural and political spheres. In less than half a century, the millionaire class has crushed organized labor and disenfranchised millions while constraining political organization into two corporate-run political parties. They have demonized the very idea that a society should be run by anyone other than banks and corporations. And as more horrific legislation and court cases (such as Janus v AFSCME) loom overhead, things seem like they are going to get worse before they get any better.

Deeply transformative revolutions must be people-powered, and we are far from having that scale of a base at this moment in history. Take the the Russian Revolution, where the transformative process was driven by workers and peasants. Petrograd alone had hundreds of thousands unionized workers who had years of practice with strikes and workplace governance when they took the streets to overthrow their provisional government in 1917. Right now, the labor movement in the United States only has 11% union density, and it is limited by a gross lack of rank-and-file governance. If liberation is to come through a direct confrontation with corporate power, we’re a long way from building enough power to engage in that struggle in a meaningful way.

Learning from our past

Decades of corporate dominance has nearly erased the proud history of worker organizing and long standing traditions of grassroots governance and civic engagement in the United States,, whether it’s the Black Panthers’ free breakfast programs and health clinics, the Congress of Industrial Organization’s militant mine and factory strikes, or the Communist Party’s brave organizing in the Black Belt. Even the universally known Civil Rights Movement has been reduced to a white-washed story of civility that is severed from its revolutionary economic demands. As the fires of popular political struggle have faded, the civic engagement that once fueled them has long been reduced to a dimly-lit ember. This has left our movements facing the task of gathering tinder so we can light the flames anew. Currently, we’re faced with communities and neighborhoods that are struggling, facing deep division, alienation, and hopelessness.

Electoral organizing offers us a strategic starting point where we can take up the work of restoring our culture of civic engagement by building our organizations. Voting and formal governance are the only reference that most americans have for political power and organization. Electoral organizing is political struggle at its most immediately visible and accessible, and it can serve as a pathway to educate and agitate our communities. New volunteers within Lancaster Stands Up, for example, intuitively understand the strategy of registering voters. As they knock on doors and talk to other working people, our members quickly learn why so many people aren’t politically active. Countless poor and working families have been alienated from the Democratic Party and the practice of voting itself. As an independent political organization, we’re in the position to speak frankly to that alienation. We can talk about how neither party actually stands for working people, especially people of color. We can make the case that this is why our organization exists in the first place: to provide an independent base to build power to meet the real needs of our communities.

Unlike narrow issue campaigns, electoral campaigns allow organizations to put forward an entire platform of issues and to make concrete demands regarding each one. This serves as an opportunity to expand people’s political consciousness, and it helps to build a wider base by capturing the involvement of folks who otherwise are only moved into action by individual issues.

In an effort to shift wider political culture and narratives. Lancaster Stands Up expresses our platform through the progressive populist framing of “Lancaster Values”, telling a story of the community’s historical Mennonite roots and working to reset the common narrative of small town christian conservatism. Through this frame, we advance the story that Lancaster was founded on the idea that we should “Love thy neighbor as thyself.” These foundational values encourage us to embrace immigrants and refugees, dismantle racism, and ensure healthcare.. Not only does this define our organization’s policies and internal values; it enables us to lay claim to the majority of the populace as a natural base for our movement. It turns Congressman Smucker into the radical minority, holding up a mirror on how far his racist pro-corporate agenda strays from the values that he claims to live by.

On the ground in Pennsylvania

Electoral organizing has been a key vehicle that has allowed us to build our organization, Lancaster Stands Up. On the whole, electoral organizing is best utilized when it’s seen as an engine to power ongoing movement work. This is a strategy known as Movement Politics. It’s an attempt to look beyond typical short-term transactional electioneering and use political campaigns to build the profile of organizations, shift the political narrative, forward policy and a long term progressive vision, and exercising power through accountability structures, along with so much more. I.

There is perhaps no greater example of this approach than Reclaim Philadelphia, an organization that was formed out of the Philadelphia Bernie Sanders Campaign office in order to build on the base building, leadership development, and infrastructure that had developed throughout the election. Reclaim is the main force that was responsible for the election of Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, They asked him to run, and they knocked on 90,000 doors to ensure his victory. While DA races usually fly under the radar and have low voter turnout, this campaign was different. Krasner’s campaign highlighted Philadelphia’s status as America’s ‘most incarcerated city.’ It made once radical views on criminal justice mainstream. His opponents continuously drifted left as the campaign became a contest to become the most progressive candidate.

When Krasner won, Reclaim became a key player in the Coalition for a Just DA, a set of organizations that regularly meets with Krasner to hold him accountable to their vision for the criminal justice system. his campaign helped expand Reclaim’s power more broadly. One of their candidates, Elizabeth Fiedler, won a contested Democratic Primary for the Pennsylvania State House. In the same election, they won about 200 Democratic committee seats. They elevated two members into Ward Leadership, granting them a direct role in determining the direction of the Philadelphia Democratic Party.

Improve people’s lives, build people’s power

Winning these campaigns and actually enacting policy that will improve people’s lives is the primary goal of engaging in electoral contests. In the case of Larry Krasner, one electoral campaign accomplished what might have otherwise taken years of different issue campaigns. This use of governing power to enact deep structural reforms can be key in our efforts to lessen the burden on poor and working families. Similarly, we could wield these tools to win universal healthcare and free higher education, to expand abortion access, to dismantle the military/prison industrial complex, and to make food, shelter, and employment available to all. These reforms, would return significant amounts of wealth from the pockets of the rich back to our communities.

But our work is not just about making short-term gains to improve people’s lives in the here and now. These kinds of victories can help to widen our bases and to make it more possible to move forward to more radical tactics and strategies. Winning real, tangible improvements will set us up to demand even more change.

If we approach them correctly, even our losses can help move our work forward. Iowa Student Action organizer Ross Floyd says that his organization’s involvement in Cathy Glasson’s progressive campaign for Governor was ultimately worth it, despite the fact that Glasson lost the Democratic primary, taking third place. “We built infrastructure, expanded our base, and developed our leaders at a scale that couldn’t have happened without this campaign,” says Floyd, noting that in the last 4 days before the election alone, “Iowa State Student Action staffed 140 shifts, made 7,663 phone calls/door knocks, had 1,663 conversations, and identified 839 Glasson supporters.”

He also speaks to the limits and frustrations of electoral organizing, making the case that elections have been designed to play to the strengths of our opponents. Floyd says, “A millionaire essentially bought the election. He spent $7 million of his own money to buy ads that completely drowned out our narrative. A single campaign cycle isn’t nearly long enough to combat that kind of money.” But he argues that makes the involvement of movement organizations all the more vital.

According to Floyd, the other tactics and strategies we have at our disposal can work in concert with electoral organizing, and all mutually benefit one another. “We can play outside the experience of opposition and organize before and after campaigns to deepen our narrative, and up our chances to actually winning elections. We need deep long-term organizing that builds relationships and aggressively uses direct action to bring the crisis of day-to-day life into the spotlight. But it’s governing power that will maintain our victories and lead us toward deeper change.”

Winning this deep change demands a diversity of strategies and tactics. We need people to organize communities so they can block ICE officers from detaining our neighbors and coworkers. We need tenants to have the power to occupy apartment buildings so that slumlords take care of tenants instead of exploiting or evicting them. We need blast the horrors that our current system to the forefront of public consciousness, creating an inflection point that forces our communities and our leaders to decide which side of the struggle they’re on. Doing so will help us move toward boldly and strategically taking governing power, which will in turn open up even more space to organize entire communities and workplaces and will move us to the point where engaging in alternate modes of resistance – like strikes, occupations and blockades- becomes as well-understood and everyday of a political action as voting is today.

To get to that point, different organizations will play different roles. Some will engage elections, others will primarily focus on direct action, educational efforts or community service. Collaboration and coordination between organizations with these different priorities can produce a radical ecosystem that is greater than the sum of its parts. A one-two punch – inside and outside of the electoral arena – can push all of our work forward and open a path toward a world that will work for all of us.