More than 40 years later the world is once again experiencing the tremors of large-scale, global change. And the prison accompanies this new burst of struggle. For a generation that has never known an America without mass incarceration, never known a world without Guantanamo and Abu Ghraib, without indefinite detention and pre-emptive war, the prison may seem an even more fitting metaphor for the contradictions of American power – internationally and within the United States – than it was during the 1971 Attica rebellion, the most dramatic of the dozens of riots rocking American prisons during that time. When prisoners at Attica proclaimed their humanity against the brutality of the prison, the United States incarcerated some 300,000 people. Today it imprisons more than 2.3 million, often serving Draconian sentences, with another 5 million under some form of correctional control. The scale of America’s carceral state is even more gruesome when one considers the demographics of those incarcerated: almost exclusively poor, majority black or Latino, and with women and gender-nonconforming people being hard hit both by incarceration and its collateral consequences.

Prisoners themselves are crucial participants – if often unacknowledged by the outside world – in the renewed activism most commonly associated with the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street. The conditions of confinement have given a life-or-death character to much of this activism. Massive labor strikes shook Georgia prisons in December 2010, coordinated through smuggled cell phones. The next month, five prisoners in Ohio launched a hunger strike to protest their conditions; a year-and-a-half later, other prisoners in Ohio’s “supermax” facilities also staged a hunger strike over inhumane conditions. Between July and October 2011, thousands of prisoners throughout the sprawling California prison system staged an unprecedented hunger strike in protest of the long-term solitary confinement that is now a significant part of everyday life in American prisons. The hunger strike seems to be emerging as a tactic of this burgeoning collective discontent with confinement; in May 2012, prisoners in Virginia’s supermax prison at Red Onion launched their own hunger strike, issuing 10 demands for better conditions, modeled after the five demands raised by California prisoners a year previously.

Then as now, the prison is a global icon of oppression. The detention facilities at Guantanamo and Bagram Air Base continue to draw international condemnation. More than 2000 Palestinians in Israeli prisons staged a hunger strike for between four and nine weeks in the spring of 2012 to protest the conditions of their detention. Self-described political prisoners in Cuba have likewise engaged in hunger strikes to protest the denial of human rights and basic freedoms. And in much of Latin America, notoriously overcrowded and violent prisons are drawing new, critical attention.

The new prison protest in the United States confronts the particularities of mass incarceration, while calling upon a deeper history of prison resistance. Although it may seem as if each political generation discovers its mission in an historical void, reality is more dialectical. With varying degrees of awareness, movements emerge in contexts established partially by prior movements, enabling conversations with various legacies of struggle.

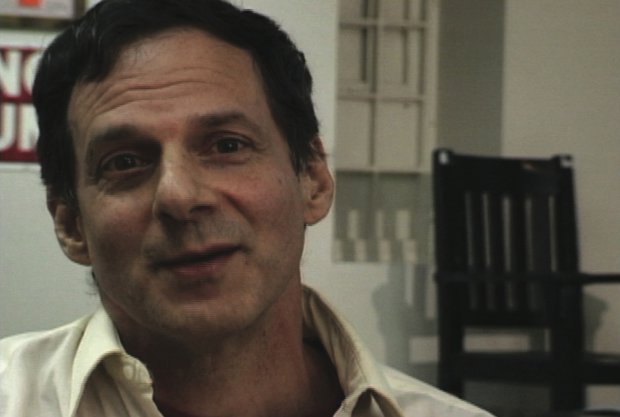

The following interview with David Gilbert is one attempt at such an intergenerational conversation across prison walls. David Gilbert was a founder of Columbia University’s Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter. His campus organizing for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam in the first half of the 1960s helped lay the foundation for the historic student strike at Columbia University in the spring of 1968. Part of the so-called “praxis axis” of SDS, Gilbert developed a reputation as a theorist and writer. He co-authored the first pamphlet within the 1960s student movement to explain the Vietnam War and American foreign policy more broadly in terms of imperialism. In 1970 he joined the Weather Underground, a militant and clandestine offshoot of SDS. The group pledged its solidarity with the black freedom struggle and national liberal movements of its day. It claimed responsibility for two dozen or so bombings of empty government and corporate buildings between 1970 and 1976, done to protest American political-economic violence throughout the world – including inside US prisons. Gilbert was one of several people who returned underground after the group disbanded in 1977. He was arrested in Nyack, New York, in October of 1981 following a botched robbery of a Brinks truck by the Black Liberation Army, itself an offshoot of the Black Panther Party. Two police officers and a security guard were killed in the robbery. An unarmed getaway driver there as a white ally, Gilbert was charged under New York’s felony murder law that holds any participant in a robbery fully culpable for all deaths that occur in the course of that robbery. The judge sentenced him to serve between 75 years and life in prison. Under current New York state law, there is no time off for good behavior, no parole possibilities in a sentence such as his.

During his more than 30 years in New York state’s toughest prisons, Gilbert has published several pamphlets on race and racism, social movement history, and the AIDS crisis. He helped start, in the 1980s, the first comprehensive peer education program in New York prisons dealing with HIV/AIDS prevention. He appeared in the 2003 academy award-nominated documentary The Weather Underground and corresponds with dozens of activists throughout North America. He has also published two books: a 2004 collection of essays and book reviews entitled No Surrender: Writings from an Anti-Imperialist Political Prisoner, and the 2012 memoir Love and Struggle: My Life in SDS, the Weather Underground and Beyond. The memoir offers David’s examination of his life as an organizer and the choices that ultimately led him to prison – an assessment of the paths taken and not taken, of the triumphs and mistakes made in a life on the left. Writing for today’s generation of activists, Love and Struggle is his attempt to summarize the lessons he learned as an organizer in SDS, in the Weather Underground, and, well, beyond.

This interview is principally concerned with the “beyond.” A voracious reader, Gilbert has been paying close attention to the recent uprisings that have dotted the globe. In the discussion below, Gilbert offers his perspective as an activist for more than 50 years, on the challenges for contemporary social movements.

This interview was conducted through the mail between February and July of 2012. I have, where appropriate, added explanatory footnotes or parenthetical notes.

Berger: Since the fall of 2011, the Occupy movement has emerged in the United States, joining many similar movements against austerity worldwide and now creating its own ripples. Its participants are disproportionately white and include many college students or graduates struggling with student debt. You’ve offered supportive statements to the Occupy movement while also trying to call its attention to other issues and dynamics. What do you see as its existing strengths, its potential, and its limitations of perspective?

Gilbert: The Occupy movement is a breath of fresh air. After 30 years of mainstream politics totally dominated by racially coded scapegoating – you know, directing people’s frustrations against welfare mothers, immigrants, and criminals – finally a loud public voice is pointing to the real source of our problems. And I think they were wise, despite the conventional wisdom of many organizers, not to come out immediately with a set list of demands. That would have narrowed the scope of support, and holding back on specifics implies that the issue is the system, capitalism, itself. There are now plenty of opportunities – through demonstrations, teach-ins, occupations, whatever – to show the range of ways this system is oppressive and destructive.

At the same time, such a spontaneous and predominantly white movement will inevitably have giant problems of internalized racism and sexism. I couldn’t help but notice that the first public statement that came out of the general assembly of OWS talked eloquently, and quite rightly, about the injustice of animals being kept in cages … but said nothing about the 2.3 million human beings in cages in the US today, with mass incarceration the front line of the 1%’s war against black and Latino/a people. And then there is the terminology of “occupy,” which does invoke a certain militant tradition, but people need to be aware of the colossal injustice that we are living on occupied Native American land. So far there has been little about the 1%’s rule over a global economy, wreaking terrible destruction on the vast majority of humankind. And that’s the basis for why the USA is now engaged in pretty much continual warfare, which not only is tremendously damaging to the people who get bombed but also reinforces all the reactionary trends here at home. So it’s vitally important that we oppose those wars.

Also I’ve heard that at many of the assemblies the speakers are almost all males. So the problems of white and male supremacy are endemic and usually prove debilitating. But flowing streams of protest provide a lot healthier basis for growth than the previously stagnant waters; people in motion against the system are a lot more open to learning. And in particular I want to salute the people of color (POC) groupings who, despite how galling some of the backwardness must be, have hung in there and struggled – groups like the POC Working Group at Occupy Wall Street and Decolonize Portland and the very strong POC presence and role in Occupy Oakland. So the 20 February 2012 day of protests in support of prisoners and the 19 April 2012 teach-ins about mass incarceration are important steps forward. There is still a long, long way to go, but overall I feel very heartened, even excited, by this new wave of protests.

Berger: In writings and interviews since your incarceration, you have described the radical potential of the 1960s era as being rooted in a combination of the success of anticolonial revolutions in the Third World and the centrality of the black freedom struggle within the United States. We are now in an era of renewed global struggle, yet the terms have changed. How would you characterize the tenor and impact of this global upsurge? How do you see it in relation to, or even as a commentary upon, the successes and limitations of earlier national liberation movements?

Gilbert: We still live in a world of totally intolerable destruction and demeaning of human life and of the environment. The most oppressed and vast majority of humankind live in the global South, and they tend to be the most conscious and most active against the system. The national liberation struggles that lit the world on fire in the 1960s and 1970s were not able to fully transform the conditions and lives of their peoples. Learning from the setbacks, people are trying to fight in ways that are less top–down, with stronger democratic participation. So it makes sense that new forms of struggle have emerged, like rural communities resisting dams in India, which combine the needs of poor farmers, the leadership of women, and critical environmental issues; or like the taking over of factories in Argentina.

In the past year-and-a-half, the “Arab Spring” has electrified the world. These mass uprisings for democracy in countries hit hard by neoliberalism in Northern Africa and the Middle East have been tremendously exciting and were a big inspiration for the Occupy Wall Street movement in the USA. But it’s important to recognize both the pluses and minuses of this kind of spontaneity. The strength is that even in situations where all organized opposition was crushed, people found a powerful way to rise up. The weakness lay in an inadequate analysis and program on the nature of the State, especially the role of the military, for example in Egypt, and its very close ties to the Pentagon. Such mass outpourings, as we also saw with “people’s power” in the Philippines in 1986, are not in themselves adequate to liberate people from the stranglehold of imperialism.

And imperialism is never a passive spectator but rather employs its massive resources and wealth of techniques to distort and reshape such movements: from funding pro-western elements with major infusions of cash to the ways the global corporate media defines the issues, from direct trainings of favored groups to covert CIA operations to outright military involvement. Libya is a recent example. Qaddafi was a tyrant, even while more progressive in terms of health, education, and the status of women than the US-imposed and backed dictators of the region. NATO’s “humanitarian” intervention killed far more of the civilians they were mandated to “protect” than did the old regime. It seems clear that the massive, destructive NATO military intervention was not wanted nor requested by the overwhelming majority of Libyans, regardless of their stance on the Qaddafi regime. The brutal bombing campaign and the empowering of factions favorable to NATO may well lead to the USA getting its long-coveted military base in Africa.

In Iran and Syria, the repressive regimes are in big part a result of earlier imperialist interventions, while the current international campaigns against them are very much about strengthening the USA and Europe’s geopolitical position. Genuine people’s opposition forces are undermined and caught in the cross-fire, while imperialist proxy forces proliferate.

In this complicated world, our loyalty is always with the people. We can’t glorify tyrants just because they come into conflict with the West but neither can we forget that imperialism is by far the greatest destroyer of human life and potential. We have to be ready to cut through the rationalizations about “weapons of mass destruction” or “terrorism” or “humanitarian emergency” and oppose what is now a pretty much constant state of warfare against countries in the South – which is brutal for the peoples attacked and also serves to reinforce all the reactionary trends here at home. Many current situations are very painful, with no major organized force of “good guys” to root for – from Assad’s killing of civilians to the Taliban’s misogyny. But to respond in an effectively humanitarian way, we have to study history. It is the West, first with colonialism and then innumerable CIA interventions, that has decimated Left secular forces who could build unity an